齐泽克2024新书《基督教无神论:如何做一个真正的唯物主义者》

AI 大纲

这本书内容丰富且多元,涵盖了多个领域,从哲学、心理学、政治、宗教到文化批评,以下是对书中主要议题的总结:

-

基督教无神论的探讨:书中深入分析了基督教无神论的概念,即在摒弃传统宗教框架的同时,吸收基督教中激进的社会和道德理念,将其转化为一种唯物主义的政治实践。齐泽克通过分析《十二》这首诗的社会影响,展示了革命行动中神学与政治的交织,强调基督形象的象征性而非实质性的存在,如何激励无神论者在无神的世界中为共同事业奋斗。

-

社会与政治批判:书中通过讨论诸如以色列与巴勒斯坦冲突、美国政治中的极端言论等实例,批判了现代政治中的暴力和不公,同时也审视了政治正确、身份政治以及现代西方社会中的自由主义困境。齐泽克指出,真正的唯物主义需要超越这些表面现象,触及社会结构的本质。

-

科学技术与唯物主义:书中探讨了科学与唯物主义的关系,特别是科学如何揭示现实的不一致性,如通过量子力学、天体物理学等领域的例子,展示了科学对传统物质观的挑战。齐泽克引用拉康的理论,讨论了“无物”概念,即科学揭示的非物质性物质效应,以及它们如何改变我们对现实的理解。

-

文化和艺术的反思:书中还涉及了文化和艺术对现代生活的意义,如对《双身》电影的分析,显示了身份、忠诚与背叛的复杂性,以及艺术作品如何反映和批判社会现实。齐泽克通过对侦探小说、电影和其他文化产品的讨论,展现了艺术作为现实批判和意识形态揭示工具的作用。

-

个人与集体的主观性:通过分析歇斯底里人格的心理特征,书中探讨了个体在社会大他者中的位置,以及个体欲望与社会结构之间的关系。齐泽克利用拉康的理论,指出个人欲望往往是对社会秩序不满的表达,而歇斯底里则是一种对社会大他者不完整的感知和反应。

-

全球政治与意识形态:书中还对中国的政治制度、人工智能的伦理问题、全球政治经济结构等进行了评论,讨论了现代科技、全球化对个人自由和社会秩序的影响,以及如何在无神论视角下理解这些现象。

综上所述,这本书是一部跨学科的理论作品,齐泽克以其独特的哲学视角,将基督教无神论置于广泛的社会、政治和技术背景中进行考察,提出了对现代世界深刻而批判性的思考。

《基督教无神论:如何做一个真正的唯物主义者》

INTRODUCTION : WHY TRUE ATHEISM HASTO BE INDIRECT

简介 :为什么真正的无神论必须间接进行?

I am not only politically active but often also perceived as politically radioactive. The idea that political theology necessarily underpins radical emancipatory politics will for certain add to this perception.

我不仅在政治上活跃,而且往往被视为具有政治上的“放射性”。政治神学必然支持激进的解放政治的想法,无疑会加强这种看法。

The basic premise of atheists today is that materialism is a view which can be consistently exposed and defended in itself, in a positive line of argumentation without references to its opposite (religious beliefs). But what if the exact opposite is true?

今天无神论者所持的基本前提是,唯物主义是一种可以独立地一贯地阐述和辩护的观点,它本身不需要借助与之相反的(宗教信仰)来论证。但是如果正好相反的情况是真实的呢?

What if, if we want to be true atheists, we have to begin with a religious edifi ce and undermine it from within? To say that god is deceiving, evil, stupid, undead . . . Is much more radical than to directly claim that there is no god: if we just posit that god doesn’t exist, we open up the way towards its de facto survival as an idea(l) that should regulate our lives. In short, we open up the way to the moral suspension of the religious.

如果我们想要成为真正的无神论者,我们是否必须从宗教建筑开始,从内部对其进行削弱?说上帝是欺骗、邪恶、愚蠢、不死的……比直接宣称上帝不存在要更激进得多:如果我们只是假定上帝不存在,就会为宗教观念继续存在留下道路。简而言之,我们为道德上对宗教的悬置打开了道路。

Here one should be very precise: what one should reject unconditionally is the Kantian view of religion as a mere narrativization (presentation in the terms of our ordinary sensual reality) of the purity of moral Law. In this view, religion is for the ordinary majority who are not able to grasp the suprasensible moral Law in its own terms.

这里应该非常精确:人们应该无条件地拒绝的,是康德关于宗教仅仅是对道德法则纯洁性(以我们日常感性现实的术语表述)的叙事化(presentation)的观点。在这种观点中,宗教是为了普通大众的,他们无法以超感性的方式把握道德法则。

What one should insist on, against this view, is that religion can in no way be reduced to this dimension, not only in the sense that it contains an ontological vision of reality (as created by God(s), regulated by divine providence, etc.), or in the sense of intense religious and/or mystical experience which reaches well beyond morality, but also in the immanent sense.

有人认为宗教只具有这种维度,对此应该坚持的是,宗教不仅在存在论的层面上包含现实(由神创造、受神意支配等)的意义,或者在强烈的宗教和/或神秘体验的意义上超越道德,而且还在内在的意义上具有这种维度。

Just recall how often, in the Old Testament, God appears unjust, cruel, and even frivolous (from the book of Job to the scene of imposing circumcision Is Christianity itself not unique among religions due to the fact that it cannot be accessed directly but only through another religion (Judaism)? Its sacred writing – the Bible – has two parts, the Old and the New Testament, so that one has to go through the fi rst one to arrive at the second one.

在旧约圣经中,上帝经常以不公正、残忍甚至轻率的方式出现(从《约伯记》到令人印象深刻的割礼场景)。基督教本身不是由于它不能直接接触,而只能通过另一种宗教(犹太教)来接触,而成为宗教中独一无二的吗?它的神圣著作——圣经——分为两部分,旧约和新约,因此人们必须先通过旧约才能到达新约。

Back in 1965, Theodor Adorno and Arnold Gehlen held a big debate ( Streitgespraech , as they call it) on German public TV 2 ; while the topic Circulated around the tension between institutions and freedom, the actual focus of the debate was: is truth in principle accessible to all or just to the selected? The interesting paradox was that, although Adorno’s writings are almost unreadable for those non-versed in Hegelian dialectics, he advocated the universal accessibility of truth, while Gehlen (whose writings are much easier to follow) claims that truth is accessible only to the privileged few since it is too dangerous and disruptive for the crowd of ordinary people. If the problem is formulated in these general terms, I am on the side of Adorno: truth is in principle accessible to all, but it demands a great effort of which many are not able. However, I would like to advocate a much more precise thesis. In an abstract sense of scientifi c “objective knowledge” our knowledge is of course limited – for the large majority of us it is impossible to understand quantum physics and higher mathematics. But what is accessible to us all is the elementary move from our experience of lack (our imperfect universe, the limit of our knowledge) to redoubling this lack, i.e., locating it in to the Other itself which becomes a “barred” Inconsistent Other. Hegel’s notion of God provides the exemplary case of such a redoubling: the gap that separates us, fi nite and frail sinful humans, from God, is immanent to God himself, it separates God from himself, making him inconsistent and imperfect, inscribing an Antagonism into his very heart. This redoubling of the lack, this “Ontologization” of our epistemological limitation, is at the core of Hegel’s absolute knowing, it signals the moment when Enlightenment is brought to its end.

早在 1965 年,西奥多·阿多诺和阿诺德·盖伦在德国公共电视上举行了一场大型辩论(他们称之为“争吵”);虽然话题围绕着制度和自由之间的紧张关系,但辩论的实际焦点是:原则上所有人都能获得真理,还是只有被选中的人才能获得?有趣的是,尽管阿多诺的著作对于那些不熟悉黑格尔辩证法的人来说几乎无法阅读,但他主张真理对所有人来说都是普遍可得的,而盖伦(他的著作很容易理解)认为只有少数特权者才能获得真理,因为它对普通人来说太危险和破坏性。如果问题用这些一般术语来表述,那么我会站在阿多诺一边:真理在原则上是所有人都能获得的,但它需要付出巨大的努力,许多人无法做到。然而,我想提出一个更加精确的论点。从科学的抽象意义上说,“客观知识”,我们的知识当然是有限的-对于我们大多数人来说,不可能理解量子物理学和高等数学。但是,对我们来说都是可用的,是从我们对缺乏的经验(我们的不完美的宇宙,我们的知识的极限)到增加这种缺乏,即将其定位在自身中成为“禁止的”不一致的另一个自我。黑格尔的上帝概念提供了这样一个增加的典型例子:将我们分隔开、有限的、脆弱的有罪人类与上帝之间的鸿沟,存在于上帝自身之中,使上帝自己与自己分离,使他变得不一致和不完美,在他的内心深处烙印着一种对抗性。这种增加的缺乏、这种我们的认识论局限的“本体化”,是黑格尔绝对认识的本质所在,它标志着启蒙走向终结的时刻。

All chapters are interventions in an ongoing debate. In (1) I propose my own solution to the dialogue between Lorenzo Chiesa and Adrian Johnston about psychoanalysis and atheism; in (2) I reply to my Buddhist critics who claim that I miss the proximity between Lacan and Buddhism; in (3) I deal with confl icting philosophical interpretations of Quantum mechanics; in (4) I engage in a dialogue with Alenka Zupan cˇ i cˇ About Antigone, the sacred and the obscene, against the humanist reading of Antigone’s act as a demand for inclusion of all marginalized minorities into the human universality; in (5) I try to dispel some misunderstandings that blur the actual social and subjective effects of Artifi cial Intelligence; last but not least, in (6), I promote my thesis on the need for theology in radical politics against the standard advocacy of materialist politics of emancipation. In spite of this dialogical character, the book follows a very precise line: from the basic determination of my Christian atheism, through outlining the difference between my atheism and Buddhist agnosticism, asserting the deep atheism of quantum Physics, an exploration of the triangle of divine, sacred and obscene, and a materialist critique of the anti-Christian spiritual reading of Artifi cial Intelligence, up to an explanation of why emancipatory politics doesn’t work without theological (or, more precisely, theosophical) dimension.

所有章节都是对持续辩论的干预。

在 (1)中,我提出我对洛伦佐·切塞和阿德里安·约翰斯顿之间关于精神分析和无神论的对话的解决方案;

在 (2)中,我回应我的佛教批评者,他们声称我错过了拉康和佛教之间的亲近关系;

在 (3)中,我处理对量子力学导言的哲学解读冲突;

在 (4)中,我与阿伦卡·祖帕尼奇对话讨论安提戈涅、神圣和猥亵的问题,反对将安提戈涅的行为解读为人本主义,将其视为要求将所有边缘化的少数群体纳入人类普遍性的要求;

在 (5)中,我试图消除一些误解,这些误解模糊了人工智能的实际社会和主观影响;最后但并非最不重要的,

在 (6)中,我主张激进政治需要神学,反对解放的唯物主义政治的标准倡导。尽管这本书具有对话性,但其路线非常明确:从我的基督教无神论的基本决定出发,通过概述我的无神论与佛教不可知论之间的区别,坚持量子物理学的深刻无神论,探索神圣、神圣和猥亵的三角形,对人工智能的反基督教精神解读进行唯物主义批判,一直到解释为什么没有神学(或更精确地说,灵性)维度的话,解放的政治就不会起作用。

So let me provide a clear and condensed description of this book’s basic premises. I try to bring together three recurrent themes of my work which, that’s my hypothesis, turn out to be three aspects of the same nucleus: the atheist core of Christianity; ontological implications of quantum mechanics; transcendental/ontology parallax.

那么,让我对这本书的基本前提作一简明扼要的说明。我试图把我这工作的三个反复出现的主题汇集在一起,据我推测,这三个主题其实是同一个核的三个方面:基督教的无神论内核;量子力学在本体论上的含义;超越论/本体论的视差。

What makes Christianity unique is how it overcomes the gap That separates humans from god: not by way of humans Elevating themselves to god through pious activity and Meditation and thus leaving behind their sinful lives, but by way of transposing this gap that separates them from god into god Himself. What dies on the cross is not an earthly representative or messenger of god but, as Hegel put it, the god of the beyond Itself, so that the dead Christ returns as Holy Ghost which is Nothing more than the egalitarian community of believers (as Paul put it, for Christians, there are no women and men, no Greeks and Jews, they are all united in Christ). This community Is free in the radical sense of being abandoned to itself, with no transcendent higher power guaranteeing its fate. It is in this Sense that god gives us freedom – by way of erasing itself out of the picture.

基督教的独特之处在于它如何克服了人类与上帝的差距:不是通过人类提升自己上帝通过虔诚的活动和冥想,从而留下罪恶的生活,但通过转换这个差距,把他们从上帝变成上帝自己。死在十字架上不是一个世俗的代表或上帝的信使,但正如黑格尔所说,神本身,所以死去的基督返回圣灵只不过是平等社区的信徒(保罗所说,基督徒,没有女人和男人,没有希腊人和犹太人,他们都是联合在基督)。这个社区是自由的,在激进的意义上被自己抛弃了,没有卓越的更高的权力来保证它的命运。正是在这个意义上,上帝给了我们自由——通过把自己从画面中抹去。

The ontological implications of quantum mechanics point – not towards a deceiving god, as Einstein thought, but – towards a god who is himself deceived. “God” stands here for the big Other, (for Einstein) the harmonious order of laws of nature which are eternal and immutable, allowing no exception, part of objective reality that exists independently of us (human observers). The basic insight of quantum mechanics is, on the contrary, that there is a domain (whose status is disputed) of quantum waves where chance is irreducible, where things happen which can be retroactively annihilated, etc. – in short, a domain that escapes the control of the (divine) big Other (information travels faster than light, etc.). When this insight was combined with the idea that quantum oscillations collapse into our ordinary reality only when an observer perceives and/or measures them, this is usually read as an argument against materialism, against the view that reality exists out there independently of us – some even propose god as the ultimate observer which constitutes reality. My thesis is, however, that Einstein was right in designating the big Other of natural laws as “divine” – a truly radical materialism does not reduce reality to what we perceive as our everyday external world, it allows for a domain which violates natural laws.

量子力学的本体论含义——不是像爱因斯坦所认为的那样指向欺骗神明,而是指向一个自身受骗的基督教无神论神明。“上帝”在这里指的是大他者,(对爱因斯坦来说)是永恒不变的自然法则的和谐秩序,不允许有例外,是独立于我们(人类观察者)而存在的客观现实的一部分。量子力学的基本洞见恰恰在于,存在一个量子波的领域(其地位尚有争议),在这个领域中,偶然是无法消除的,会发生一些事后可以被消灭的事情——简而言之,一个领域,它超出了(神性)大他者的控制(信息传播比光速还快等等)。当这一洞见与量子振荡只有在被观察者和/或测量时才会坍缩到我们普通的现实中的观念相结合时,通常被解读为反对唯物主义的论据,反对那种认为现实独立于我们而存在的观点——有些人甚至主张上帝是构成现实的终极观察者。然而,我认为爱因斯坦将自然法则的大他者称为“神”是正确的——真正的激进唯物主义并不会将现实简化为我们感知到的日常生活外部世界,它允许存在一个违反自然法则的领域。

The biggest cut in the history of philosophy takes place with Kant’s transcendental revolution. Till Kant, philosophy (no matter how sceptic) was dealing with the ontological dimension in the simple sense of the nature of reality: what counts as reality, can we know it, how is this reality structured, is it only material or also, even primarily, spiritual, etc. With Kant, reality is not simply given, waiting out there to be discovered by us, it is “transcendentally constituted” by the structure of categories through which we apprehend it. After Kant, this transcendental dimension is historicized: every epoch has its own way of perceiving reality and acting in it. For example, modern science emerged once reality was perceived as the space of external material existence regulated by its laws, and reality was thus strictly separated from our subjective feeling and projections of meaning. Parallax means here that the two approaches are irreducible to each other and simultaneously imply each other: we can investigate reality as an object and explain its evolution, up to the emergence of human life on earth, but in doing this, we already approach reality in a certain way (through evolutionary theory and its concepts) which cannot be deduced from its object but is always-already presupposed (we presuppose that nature is regulated by complex causal links, etc.).

哲学史上最大的变革发生在康德的先验革命中。在康德之前,哲学(无论多么怀疑论)都处理实在的本体论维度,即现实的本性:什么是现实,我们能知道什么,现实是如何结构的,它仅仅是物质的还是首先也是精神的等等。在康德那里,现实不仅仅简单地给予,等待我们去发现,它是我们通过范畴的结构“先验地构成”的。在康德之后,这种先验维度被历史化了:每个时代都有自己感知现实和在其中行动的方式。例如,现代科学出现的时候,现实被感知为受其定律调节的外部物质存在的空间,因此现实与我们的主观感觉和意义投射严格分开。视界叉是这两种方法不可化约而又同时相互蕴含:我们可以把现实作为一个对象来研究并解释其演变,直至地球上人类生命的出现为止;但在此过程中,我们已经以某种方式接近现实(通过进化论及其概念)而这种方式不能从其对象中推导出来,而是始终已经预设的(我们预设自然受复杂因果链调节等)。

The book brings together these three topics into a project of “Christian atheism”: the space for the experience of the “divine” is the gap that forever separates the transcendental from the objective-realist approach, but this “divine” dimension refers to the experience of radical negativity (what mystics and Hegel called “night of the world”) which precludes any theology focused on a positive fi gure of god, even if this fi gure of god is radically secularized in modern scientifi c naturalism. In Christianity, this gap registers the absence of god (its “death”) which grounds the Holy Ghost. And, last but not least, the dimension of radical negativity also holds open the space for every emancipatory politics which takes itself seriously, i.e., which reaches beyond the continuity of historical progress and introduces a radical cut that changes the very measures of progress.

该书将这三个主题汇集到“基督教无神论”这一项目之中:体验“神圣”的空间是永恒地将超越论与客观-实在论方法分开的鸿沟,但这一“神圣”维度指的是极端消极的经验(神秘主义者和黑格尔称之为“世界的黑夜”),它排除了任何以积极的神的形象为中心的神学,即使这一神像在当代科学自然主义中已被彻底去神学化。在基督教中,这一鸿沟记录了神的缺席(其“死亡”),它为圣灵提供了基础。而且,最后但同样重要的是,极端消极的维度还为严肃对待自身的每一项解放政治留出空间,也就是说,它引入了根本断裂,从而改变了进步本身的尺度。

The Self-Destruction of the West

西方的自我毁灭

But, as we learned from Hegel, moments of a dialectical process can be counted as three or as four – and the fourth missing moment is here politics, of course. (The political dimension is not limited to the fi nal chapter, it runs as an undercurrent through the entire book, popping up even in its most philosophical parts.) This brings us back to my political radioactivity – to resume it, let me begin by Jean-Claude Milner’s claim [^4] that what we call “the West” is today a confederation under the US hegemony; the US reigns over us also intellectually, but here “one has to accept a paradox: the US-American domination in the intellectual domain expresses itself in the discourses of dissent and protest and not in the discourses of order.” Global university teaches us to refuse the economic, political, and ideological functioning of the western order in part or entirely. Inequality plays the role of an axiom, from which all ultimate criticism derives. Depending on the various situations, one will privilege this or that specifi c form of general inequality: colonial oppression, cultural appropriation, the primacy of white culture, the patriarchy, the conflicts of gender and so on.

然而,正如我们从黑格尔那里学到的,辩证过程的时刻可以算作三个或四个——而这里缺失的第四个时刻就是政治,当然。政治维度并不仅仅局限于最后一章,它像一条暗流贯穿整本书,甚至在最具哲学性的部分也会冒出头来。这使我想到了我的政治放射性。为了继续这个话题,我想从让-克洛德·米尔纳的主张 4 说起,他主张我们所谓的“西方”今天是在美国霸权之下的一个联盟;美国在智力上统治我们,但在这里,“必须接受一个矛盾:美国在知识领域的统治表现在异议和抗议的论述中,而不是表现在秩序的论述中。”全球大学教导我们拒绝西方秩序在部分或整体上的经济、政治和意识形态功能。不平等起着公理的作用,从中衍生出所有终极批评。根据各种情况,人们会偏重这种或那种特定的一般不平等形式:殖民压迫、文化挪用、白人文化的优越性、父权制、性别冲突等等。

Remi Adekoya points out that research uncovered a strange fact: When the voters were asked which value they appreciate most, in the developed West the large majority chose equality, while in sub-Saharan Africa, the large majority largely ignored equality and put at the fi rst place wealth (independently of how it was acquired, even if it was through corruption). This result makes sense: the developed West can afford to prioritize equality (at the level of ideological self-perception), while the main worry among the poor majority in sub-Saharan Africa is how to survive and leave devastating poverty behind. 5 There is a further paradox at work here: this struggle against inequality is self-destructive insofar as it undercuts its own foundation, and is thus unable to present itself as a project for positive global change:

Remi Adekoya 指出,一项研究揭示了一个奇怪的事实:当选民被问及他们最欣赏哪种价值观时,发达西方的绝大多数人选择了平等,而在撒哈拉以南非洲地区,绝大多数人基本上忽视了平等,把财富放在第一位(不论财富如何获得,即使是通过腐败)。这一结果是有意义的:发达西方有能力优先考虑平等(在意识形态自我认知层面),而撒哈拉以南非洲贫穷的大多数人主要担心的是如何生存下来,摆脱毁灭性的贫困。这里存在一个更深层次的悖论:这种反对不平等的斗争破坏了自身的基础,因而是自毁性的,无法呈现为一个积极的全球变革项目:它自身就是一场零和游戏。它不仅没有带来任何积极的变化,反而加剧了不平等现象。因此,它不仅不能为那些在贫困中挣扎的人们提供希望,反而使他们更加绝望。这表明,为了实现真正的全球平等和繁荣,我们需要找到一种新的方法来处理不平等问题。我们需要找到一种方法来消除那些导致不平等现象加剧的根源,而不是仅仅关注不平等的表面现象。我们需要找到一种方法来创造一个更加公正、包容和可持续的社会环境,这将需要我们所有人共同努力来实现。

Precisely because the cultural heritage of the West cannot free itself from the inequalities that made its existence possible, past Denouncers of inequality are themselves considered to benefi t from one or another previously unrecognized inequality. . . . All the revolutionary movements and the notions of the revolution themselves are subject to suspicion now, simply because they belong to the long line of dead white males.

正因为西方文化遗产摆脱不了造成它存在可能性的不平等,过去谴责不平等的人现在也被认为从某种以前未被认识的不平等中获益……。现在所有革命运动和革命观念本身都受到怀疑,只是因为它们属于长长一串死去的白人男性。

It is crucial to note that the new Right and the Woke Left share this self-destructive stance. In late May 2023, the Davis School District north of Salt Lake City removed the Bible from its elementary and middle schools while keeping it in high schools after a committee reviewed the scripture in response to the Utah Parents United complaint, dated December 11 2022, which said: “You’ll no doubt fi nd that the Bible (under state law) has ‘no serious values for minors’ because it’s pornographic by our new defi nition.” 6 Is this just a case of Mormons against Christians? No: on June 2 2023, a complaint was submitted about the signature scripture of the predominant faith in Utah, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: district spokesperson Chris Williams confi rmed that someone fi led a review request for the Book of Mormon. Which political-ideological option is behind this demand? Is it the Woke Left (exercising an ironic revenge against the Rightists banning courses and books on US history, Black Lives Matter, LGBT+, etc.), or is it the radicalized Right itself which (quite consequently) applied their criteria of family values to their own founding texts? Ultimately it doesn’t matter – what we should note is rather the fact that the same logic of prohibiting (or rewriting, at least) classic texts got hold of the new Right as well as on the Woke Left, confi rming the justifi ed suspicion that, in spite of their strong ideological animosity, they often formally proceed in the same way. While the Woke Left systematically destroys its own foundation (the European emancipatory tradition), the Right fi nally gathered the courage to question the obscenity of its own tradition. In an act of cruel irony, the Western democratic tradition which usually praises itself for including self-criticism (democracy has fl aws, but also includes striving to overcome its fl aws . . .), now brought this self-critical stance to extreme – “equality” is a mask of its opposite, etc., so that all that remains is the tendency towards self-destruction.

必须注意的是,新右派和觉醒左派都持有这种自毁的立场。在 2023 年 5 月下旬,达拉斯学区在回应犹他州家长联合会在 2022 年 12 月 11 日提出的投诉时,将圣经从其小学和中学中删除,但保留在高中中。该投诉称:“根据我们的新定义,圣经(根据州法)对未成年人没有严肃的价值,因为它符合色情的新定义。”6 这难道只是摩门教徒反对基督徒吗?不是的:在 2023 年 6 月 2 日,有人就犹他州主流信仰的标志性圣经《后期圣徒教会》提出了投诉。该区发言人克里斯·威廉姆斯证实有人提出了审查《摩尔门经》的要求。这种需求的背后是什么政治意识形态?是觉醒左派(对禁止讲授美国历史、黑人生命、LGBT+等的右派采取讽刺报复),还是极右派本身(相当果断地)将其家庭价值观标准应用于其自身创始文本?最终这并不重要——我们应该注意到的是,禁止(或至少重写)经典文本的逻辑不仅出现在觉醒左派身上,也出现在新右派身上,证实了这样一种合理的怀疑:尽管他们有强烈的意识形态敌意,他们通常还是以同样的方式行事。觉醒左派系统地摧毁了自己的基础(欧洲解放传统),而右派最终鼓起勇气质疑自己传统的荒谬性。具有讽刺意味的是,西方民主传统通常会为自我批评(民主有缺陷,但包括努力克服这些缺陷)而自豪,但现在这种自我批评态度走到了极端——“平等”是它的反面的面具,等等,所以只剩下自我毁灭的趋势。

But there is a difference between the Western anti-Western discourse and the anti-Western discourse coming from outside: “while an anti-Western discourse is deployed within the West (and the West takes pride in this), another anti-western discourse is held outside of the West. Except that the fi rst takes inequality for a fault, which one does not have the moral right to take advantage of; the second on the contrary sees in the inequality a virtue, on the condition that it is oriented in one’s favor. Consequently, the proponents of the second anti-western discourse see the fi rst as an indication of the enemy’s decadence. They do not hide their contempt.”

西方内部有一种反西方言论(西方对此感到自豪),但另一种反西方言论却发生在西方之外。但是西方对西方的言说与来自外部对西方的言说之间存在差别:“前者是在西方内部进行(而西方以此为荣),后者则是在西方之外进行。只不过前者把不平等视为错误,这是没有道德权利占优势的;相反,后者则把不平等视为一种美德,前提是它有利于己。因此,后一种反对西方的言说者把前者视为敌人的衰败的标志。他们毫不掩饰自己的蔑视。”

And their contempt is fully justifi ed: the result of the Western anti-Western discourse is what one might expect: the more Western liberal Leftists probe their own guilt, the more they are accused by Muslim fundamentalists of being hypocrites who try to conceal their hatred of Islam. Such a paradigm perfectly reproduces the paradox of the superego: the more you obey what the pseudo-moral agency demands of you, the more guilty you are: it is as if the more you tolerate Islam, the stronger its pressure on you will be. One can be sure that the same holds true for the infl ux of refugees: the more Western Europe is open to them, the more it will be made to feel guilty that it failed to accept even more of them – by defi nition it can never accept enough of them. The more tolerance one displays towards the non-Western ways of life, the more one will be made to feel guilt for not practising enough tolerance.

他们的蔑视完全是合理的:西方反西方的言辞所产生的效果正是人们所预料的:西方左翼知识分子越是深入探究自己的罪恶感,穆斯林极端主义者就越会指责他们是伪君子,试图掩盖他们对伊斯兰教的仇恨。这种模式完美地再现了超我悖论:你越是顺从伪道德机构对你提出的要求,你越是会感到有罪:你越是容忍伊斯兰教,它对你施加的压力就会越大。可以肯定的是,难民潮也会带来同样的影响:欧洲对难民越开放,它就会感到越有罪,因为它没有接受更多的难民——从定义上讲,它永远无法接受足够多的难民。一个人对非西方生活方式表现得越宽容,他就越会感到有罪,因为他没有实践足够的宽容。

The woke radical reply to this is: the non-Western critics are right, the Western self-humiliation is fake, the non-Western critics are right to insist that whatever the West concedes to them, “this is not that,” we retain our superior frame and expect them to integrate – but why should they? The problem is, of course, that what the non-Western critics expect is, to put it brutally and directly, that the West renounces its way of life. The alternative here is: will, as the fi nal result of the Western anti-Western critical stance, the West succeed in self-destroying itself (socially, economically) as a civilization, or will it succeed to combine self-defeating ideology with economic superiority?

觉醒激进派的回应是:非西方批评者说得对,西方自我贬低是假的,非西方批评者坚持认为,无论西方给予他们什么,“这不是那个”,我们保留了优越框架并期待他们融合——但为什么他们应该这么做呢?问题在于,当然,非西方批评者所期待的是,直截了当地说,西方放弃自己的生活方式。这里的选择是:西方反西方的立场最终导致西方作为一个文明在社会和经济上自我毁灭,还是成功地将自我挫败的意识形态与经济优势相结合?

Milner is right: there is no big paradox in the fact that the self-denigrating critical mode is the best ideological stance for making it sure there will be no revolutionary threat to the existing order. However, one should supplement his claim with a renewal of (fake, but nonetheless actual) revolutionary stance of the new populist Right: its entire rhetoric is based on the “revolutionary” claim that the new elites (big corporations, academic and cultural elites, government services) should be destroyed, with violence if needed. In Varoufakis’s terms, they propose a class war against our new feudal masters – the worst nightmare is here the possibility of a pact between the Western populist Right and the anti-Western authoritarians.

米尔纳说得对:自我贬低的批判模式是确保现有秩序不会受到革命威胁的最佳意识形态立场,这是没有太大矛盾的。然而,我们应该用新民粹主义右派的(虽然虚假但依然存在的)革命姿态来补充他的观点:他们的整个言论都建立在“革命”的声明之上,即新精英(大公司、学术和文化精英、政府服务机构)应该被摧毁,必要时使用暴力。用瓦鲁法基斯的话来说,他们提议向我们新的封建主(西方民粹主义右派与反西方专制主义者之间的契约)发起阶级战争——最糟糕的噩梦就是西方民粹主义右派与反西方专制主义者之间达成协议的可能性。

In my critical remarks on MeToo as ideology, I refer to Tarana Burke, a black woman who created the MeToo campaign more than a decade ago; she observed in a recent critical note that in the years since the movement began, it deployed an unwavering obsession with the perpetrators – a cyclical circus of accusations, culpability and indiscretions: “We are working diligently so that the popular narrative about MeToo shifts from what it is. We have to shift the narrative that it’s a gender war, that it’s anti-male, that it’s men against women, that it’s only for a certain type of person – that it’s for white, cisgender, heterosexual, famous women.” 7 In short, one should struggle to re-focus MeToo onto the daily suffering of millions of ordinary working women and housewives . . .

在我对 MeToo 运动作为一种意识形态提出批评时,我提到了塔拉纳·伯克,她是一位十多年前发起 MeToo 运动的黑人女性。最近她在一篇评论中指出,自运动发起以来,它一直执着于对肇事者的关注——一个关于指责、有罪和不慎的循环马戏团:“我们正在努力改变关于 MeToo 的流行叙事,从它是什么,我们必须改变叙事,认为它是一场性别之战,认为它是反男性的,认为它是男人和女人之间的战争,认为它只适用于某些类型的人——它是针对白人、顺性别、异性恋、著名的女性。”简而言之,我们应该努力将 MeToo 重新聚焦于数百万普通劳动妇女和家庭主妇的日常苦难……

At this point, some critics have accused me of advocating a simple move from harassment in our behaviour and language to “real” socio-economic problems, (correctly) pointing out that the thick texture of behaviour and ways of speaking is the very medium of the reproduction of ideology, plus that what counts as “real problems” is never a matter of direct insight but is always defi ned by the symbolic network, i.e., it is the result of a struggle for hegemony. I thus consider the above-mentioned reproach against me a bad joke: I all the time insist on the texture of unwritten rules as the medium in which racism and sexism reproduce themselves. To put it in more theoretical terms, the big implication of “structuralist” theories (from Levi-Strauss and Althusser up to Lacan) is that ideological superstructure has its own infrastructure, its own (unconscious) network of rules and practices which sustain its functioning. However, do such “problematic” (for some) positions of mine indicate that, in the course of the last decades, I changed my position? A critic of mine recently insisted on the “contrast between (my) writing at this point (1997 when he was in his late 40s) and (my) more recent transition into a post-left fi gure” – he begins with approvingly quoting a passage from my Plague of Fantasies and then adding his comment:

此时,一些批评家指责我主张从我们的行为和语言中的骚扰行为转变为“真正”的社会经济问题,(正确地)指出行为和言语方式的浓厚质感是意识形态再现的媒介,并且被视为“真正问题”的从来不是直接洞察,而是由符号网络界定的,也就是说,它是霸权斗争的结果。因此,我认为上述对我的指责是一个恶作剧:我始终坚持不成文规则的纹理作为种族主义和性别主义自我复制的媒介。用更理论化的语言来说,“结构主义”(从列维-斯特劳斯到阿尔都塞再到拉康)理论的重要含义是,意识形态上层建筑有其自身的结构,即(无意识的)规则和惯例网络,维持其运作。然而,我的这种“令人头疼”(对一些人来说如此)的立场是否表明,在过去的几十年里,我已经改变了立场?我的一位批评家最近坚持认为“(我)写作时的立场(1997 年,那时他 40 多岁)与(我)后来转变为后左翼人物之间的对比”——他先是赞许地引用了我《瘟疫的幻想》中的一段文字,然后加上自己的评论:

If racist attitudes were to be rendered acceptable for the mainstream ideologico-political discourse, this would radically shift the balance of the entire ideological hegemony . . . Today, in the face of the emergence of new racism and sexism, the strategy should be to make such enunciations unutterable, so that anyone relying on them automatically disqualifi es himself (like, in our universe, those who refer approvingly to Fascism). One should emphatically not discuss ‘how many people really died in Auschwitz’, what are ‘the good aspects of slavery’, ‘the necessity of cutting down on workers’ collective rights’, and so on; the position here should be quite unashamedly ‘dogmatic’ and ‘terrorist’; this is not a matter for ‘open, rational, democratic discussion’.

如果种族主义的观点被纳入主流意识形态政治话语而变得可以接受,这将从根本上改变整个意识形态霸权的平衡……今天,面对新种族主义和性别主义的崛起,我们的策略应该是使这样的言论无法出口,这样任何依赖这些言论的人都会自动失去资格(就像在我们这个宇宙中那些赞扬法西斯主义的人一样)。我们不应该去讨论“有多少人在奥斯威辛真的死亡了”“奴隶制的优点”“削减工人集体权利的必要性”等等;这里的立场应该毫不掩饰地“教条主义”和“恐怖主义”;这不是一个可以进行“开放、理性、民主讨论”的问题。

Plague , p. 38

鼠疫,第 38 页

Well said. Much as for example one shouldn’t engage in conversations about whether trans women are “really” women. In fact Ž i ž ek in his late 40s holds that “the measure of ideologico-political ‘regression’ is the extent to which such propositions become acceptable in public discourse. Would he therefore see his older self as a symptom of such regression?” 8

说得对。例如,我们不应该讨论跨性别女性是否“真正”是女性。实际上,在 40 多岁时,伊利奇认为“意识形态-政治‘倒退’的尺度是这些主张在公共话语中变得可以接受的程度。因此,他会认为他年长的自己就是这种倒退的症状吗?”

My counterpoint is here an obvious one: can we really put woke and trans demands into the series of progressive achievements, so that the changes in our daily language (the primacy of “they,” etc.) are just the next step in the long struggle against sexism? My answer is a resounding NO: the changes advocated and enforced by trans- and woke-ideology are themselves largely “regressive,” they are attempts of the reigning ideology to appropriate (and take the critical edge off) new protest movements. There is thus an element of truth in the well-known Rightist diagnosis that Europe today presents a unique case of deliberate self-destruction – it is obsessed with the fear to assert its identity, plagued by an infi nite responsibility for most of the horrors in the world, fully enjoying its self-culpabilization, behaving as if it is its highest duty to accept all who want to emigrate to it, reacting to the hatred of Europe by many immigrants with the claim that it is Europe itself which is guilty of this hatred because it is not ready to fully integrate them . . . There is, of course, some truth in all this; however, the tendency to self-destruction is obviously the obverse of the fact that Europe is no longer able to remain faithful to its greatest achievement, the Leftist project of global emancipation – it is as if all that remained is self-criticism, with no positive project to ground it. So it is easy to see what awaits us at the end of this line of reasoning: a self-refl exive turn by means of which *emancipation itself will be denounced as a Euro-centric project. * 9

我的反驳观点是一个显而易见的问题:我们真的能把“觉醒”和变性人的要求纳入进步成就的系列中吗?这样一来,日常用语中的变化(“他们”的首要地位等)只是反对性别歧视长期斗争中的下一步吗?我的回答是响亮的“不”:由跨性别和觉醒意识形态所倡导和执行的变化本身在很大程度上是“退步性的”,他们是当权意识形态试图占有(并减轻)新抗议运动的批评性。因此,右派诊断欧洲今天故意自我毁灭这一说法有一定道理——它痴迷于恐惧坚持自身身份,为世界上大部分恐怖事件负无穷责任,完全享受自我归咎,认为接纳所有移民到欧洲是其最高义务,对许多移民对欧洲的仇恨的反应是欧洲自身有罪恶感,因为它不愿完全接纳他们……当然,这一切有一定道理;然而,自我毁灭的趋势显然是欧洲不再能忠于其最大成就——左派全球解放项目——的反面,仿佛只剩下自我批评,没有积极项目来支持它。因此,很容易看出这条推理线末尾等待我们的是什么:通过自我反思转向,将解放本身谴责为欧洲中心主义项目。9

With regard to slavery, one should note that it existed throughout “civilized” human history in Europe, Asia, Africa and Americas, and that it continues to exist in new forms – the white Western nations enslaving Blacks is not its most massive form. What one should add, however, is that the Western European nations (which are today viewed as the main agents of enslaving – when we hear the word “slavery,” our fi rst association is “yes, whites owning black slaves”) were the only ones which gradually enforced the legal prohibition of slavery. To cut it short, slavery is universal, what characterizes the West is that it set in motion the movement to prohibit it – the exact opposite of the common perception.

关于奴隶制,应该指出的是,它存在于欧洲、亚洲、非洲和美洲的人类整个“文明”历史中,并以新的形式继续存在——白人西方国家奴役黑人并不是其最主要的形态。然而,应该补充的是,只有西欧国家(今天被视为主要的奴隶制实施者——当我们听到“奴隶制”这个词时,我们首先想到的是“是的,白人拥有黑人奴隶”)逐渐地强制执行了禁止奴隶制的法律。简而言之,奴隶制是普遍存在的,而西方所特有的则是它推动了禁止奴隶制的运动——这与人们的普遍看法完全相反。

The title of an essay on my work – “Pacifi st Pluralism versus Militant Truth: Christianity at the Service of Revolution” 10 – renders perfectly my core of my anti-Woke Christian stance: in contrast to knowledge which relies on an impartial “objective” stance of its bearer, truth is never neutral, it is by defi nition militant, subjectively engaged. This in no way implies any kind of dogmatism – the true dogmatism is embodied in an “objective” balanced view, no matter how relativized and historically-conditioned this view claim to be. When I fi ght for emancipation, the Truth I am fi ghting for is absolute, although it is obviously the Truth of a specifi c historical situation. Here the true spirit of Christianity is to be opposed to wokenness: in spite of the appearance of promoting tolerant diversity, wokeness is in its mode of functioning extremely exclusionary, while the Christian engagement not only openly admits its subjective bias but makes it a condition of its Truth. And my wager is clear here: only the stance of what I refer to as Christian atheism can save the Western legacy from its self-destruction while maintaining its self-critical edge.

我的一篇论文的标题——“和平多元主义与好斗的真理:基督教服务于革命”——完美地表达了我反醒潮基督徒立场的核心理念:与那种依赖持有者公正的“客观”立场的认识不同,真理永远不是中立的,它从定义上讲是积极的,主观参与的。这绝非意味着任何形式的教条主义——真正的教条主义体现在“客观”平衡的观点中,无论这种观点被如何相对化和历史条件化了。当我为解放而战时,我所捍卫的真理是绝对的,尽管它显然是特定历史情境下的真理。基督教的正真精神应该反对醒潮:尽管表面上提倡宽容多元,但醒潮在其运作模式上是非常排他的,而基督教的参与不仅公开承认其主观偏见,而且将其作为其真理的条件。我在这里打赌是明确的:只有我所说的基督教无神论立场才能拯救西方遗产免于自我毁灭,同时保持其自我批评的锋芒。

Anti-Semitism and Intersectionality

反犹太主义和交叉性。

This brings us to another radioactive feature of mine: my critique of certain critiques of anti-Semitism which also mitigate the critical edge of emancipatory, universalism: they denigrate the universal dimension of Judaism precisely when they enjoin us to recognize its unique status of anti-Semitism. On May 14 2023 the European Jewish Association’s (EJA) annual conference took place in Porto, Portugal. It adopted a motion calling for antisemitism to be separated from other forms of hate and urging other Jewish groups to reject ‘intersectionality,’ a theoretical framework that separates groups into ‘oppressed’ and ‘privileged.’‘Antisemitism is unique and must be treated as such,’ according to the motion, which notes that unlike other hatreds, it is ‘state-sanctioned in many countries,’‘given cover by the United Nations’ and denied to be racism by other groups targeted by hatred. 11

这让我谈一下我的另一个辐射特征:我对某些对反犹太主义批评的批评,这些批评也减轻了解放、普遍性的批判锋芒:它们贬低了犹太教的普遍性维度,恰恰在我们要求承认反犹太主义的独特地位时。2023 年 5 月 14 日,欧洲犹太人协会(EJA)年度会议在葡萄牙波尔图举行,会议通过了一项动议,呼吁将反犹太主义与其他形式的仇恨区分开来,并敦促其他犹太团体拒绝“交集性”这一理论框架,该框架将群体分为“受压迫者”和“特权者”。根据该动议,“反犹太主义是独一无二的,必须如此对待”,并指出与其他仇恨不同,“在许多国家,它得到国家认可”,“得到联合国的掩护”,并且被其他受到仇恨袭击的群体否认是种族主义。11

The key to these claims is provided by the presumed link between three notions: the unique character of anti-Semitism, intersectionality, the opposition between the oppressed and the privileged. Why is intersectionality dismissed as “a theoretical framework that separates groups into ‘oppressed’ and ‘privileged’,” and why is this problematic from the Jewish standpoint? Intersectionality is a very useful notion in social theory and practical analysis: when dealing with an oppressed group, we discover that it can be oppressed (or privileged) at multiple intersection levels – let’s shamelessly quote a Wikipedia defi nition (because, let’s face it, it’s the defi nition most people will be using!): Intersectionality is an analytical framework for understanding how a person’s various social and political identities combine to create different modes of discrimination and privilege. Intersectionality identifi es multiple factors of advantage and disadvantage. Examples of these factors include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, religion, education, wealth, disability, weight, age, and physical appearance. These intersecting and overlapping social identities may be both empowering and oppressing. 12

这些主张的关键在于三个概念之间的假设联系:反犹太主义的独特性、交叉性以及被压迫者和特权阶层之间的对立。为什么交叉性被视为“将群体分为‘被压迫者’和‘特权阶层’的理论框架”,而且从犹太人的观点来看,这有什么问题呢?交叉性在社会理论和实际分析中是一个非常有用的概念:当我们处理一个被压迫的基督教无神论群体时,我们发现它可能在多个交叉层面上受到压迫(或享有特权)——让我们无耻地援引一下维基百科的定义(因为,面对现实吧,大多数人都会使用这个定义!):交叉性是一个分析框架,用于理解一个人的各种社会和政治身份如何结合在一起,形成不同的歧视和特权模式。交叉性识别了优势和劣势的多种因素。这些因素的例子包括性别、种姓、性别、种族、族裔、阶级、宗教、教育、财富、残疾、体重、年龄和外貌。这些交织重叠的社会身份可能既具有赋权作用又具有压迫作用。12

Consider a low-income Black lesbian: she is at a triple disadvantage almost anywhere in the world. In addition, we are never dealing just with a mechanical combination of these factors of (dis)advantage. The anti-Semitic fi gure of the “Jew” combines features of religion, ethnicity, sexuality, education, wealth and physical appearance. To be stigmatized as a “Jew” entails the attribution of a series of other features (they know how to speculate with money, they dogmatically stick to their religious rules, they are lazy and like to exploit others, they don’t wash enough . . .). The upshot of intersectional analysis is that all individuals experience unique forms of oppression or privilege by dint of the makeup of their identities. Why, then, do those who insist on the uniqueness of antiSemitism reject intersectionality?

考虑一个在世界任何地方都处于劣势的非洲裔女同性恋者:她几乎处处都处于三重劣势。此外,我们并不是仅仅在处理这些 (有利或不利的)因素之间的机械组合。反犹太人的“犹太人”形象结合了宗教、种族、性倾向、教育、财富和外貌等特征。被污名化为“犹太人”意味着被归结为一系列其他特征(他们知道如何用钱投机,他们教条地坚持自己的宗教规则,他们懒惰并喜欢剥削他人,他们洗得不够……)。结论是,所有个人都会因其身份的构成而经历独特的压迫或特权形式。那么,为什么那些坚持反犹太主义独特性的人会拒绝交叉分析呢?

The oppression faced by Jews in developed Western countries nowadays is somewhat more ambiguous, because the perception is that Jews occupy positions of privilege (economically, culturally, politically), and the association of the Jews with wealth and culture (“Hollywood is Jewish”) in the public imagination is itself a source of classic anti-Semitic tropes. The EJA worries that this combination of oppression and privileges makes anti-Semitism just another form of racial hatred, not only comparable to others but even less strong weighed alongside other modes of oppression. When we apply an intersectional lens, the hatred for “the Jew” becomes just another minor case in the broader taxonomy of hatreds. Is this fear justified?

The EJA is right in its insistence that there is something exceptional about anti-Semitism. It is not like other racisms: its aim is not to subordinate the Jews but to exterminate them because they are not perceived as lower foreigners but as our secret Masters. The Holocaust is not the same as the destruction of civilizations in the history of colonialism, it is a unique phenomenon of industrially-organized annihilation. But it is the very coupling of “oppressed” and “privileged” which provides the key to understanding anti-Semitism, at least in its modern form. Under Fascism, “the Jew” served as the external intruder who could be blamed for corruption, disorder and exploitation. Projecting the confl ict between the “oppressed” and the “privileged” onto a scapegoat can distract people’s attention from the fact that such struggles are, in fact, intrinsic to their own political and economic order. The fact that many Jews are “privileged” (in the sense of their wealth, education and political infl uence) is thus the very resource* of anti-Semitism: being perceived as privileged makes them a target of social hatred.

EJA 坚持认为反犹太主义有一些特殊之处是正确的。它不同于其他形式的种族主义:它的目的不是使犹太人处于从属地位,而是消灭他们,因为他们不被视为外来低等民族,而是被视为我们的秘密主人。大屠杀不同于殖民主义历史中的文明毁灭,它是工业化组织起来的有计划的大规模屠杀。然而,“被压迫者”和“特权者”之间的结合为理解反犹太主义提供了关键线索,至少在它的现代形式中是如此。在法西斯主义中,“犹太人”扮演着外部入侵者的角色,他们被指责腐败、混乱和剥削。将“被压迫者”与“特权者”之间的冲突投射到一个替罪羊上,可以转移人们对这样一个事实的注意力:这些斗争实际上是他们自己的政治和经济秩序的内在组成部分。因此,许多犹太人“特权”(在财富、教育、政治影响力方面)这一事实恰恰是反犹太主义的资源:他们被视为特权者,这使他们成为社会仇恨的对象。

Problems arise when one tries to use the exceptional status of antiSemitism to support a double standard, or to prohibit any critical analysis of the privileges that Jews, on average, enjoy. The title of a dialogue on anti-Semitism and Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) in Der Spiegel is: “Wer Antisemit ist, bestimmt der Jude und nicht der potenzielle Antisemit” 13 (“Who is an anti-Semite determines the Jew and not the potential anti-Semite”). OK, but should then not the same also hold for Palestinians on the West Bank who should determine who is stealing their land and depriving them of elementary rights? Isn’t apartheid sanctioned also in Israel? This is what the motion of the European Jewish Association refuses to accomplish.

当试图利用反犹太主义的特殊地位来支持双重标准,或禁止对犹太人平均享有的特权进行任何批判性分析时,就会出现问题。《明镜》杂志上的一场反犹太主义和抵制、撤资、制裁(BDS)的对话题是:“谁反犹太,谁决定犹太人,而不是潜在的反犹太人”。好吧,那么,是否也应该对西岸的巴勒斯坦人适用呢?他们应该决定谁在偷他们的土地,剥夺他们的基本权利?以色列是否也制裁了种族隔离制度?这是欧洲犹太人协会的动议拒绝达成的。

More than that, the EJA’s stance relies on its own intersectional framework. Any analysis of the privileged positions held by some Jews is immediately denounced as anti-Semitic, and even critiques of capitalism are rejected on the same grounds, owing to the association between “Jewishness” and “rich capitalists.” The good old Marxist thesis that anti-Semitism is a primitive distorted version of anti-capitalism is thus turned around: anti-capitalism is a mask of anti-Semitism. But if the implication is that Jewishness is both exceptional and inextricably bound up with capitalism, aren’t we just left with an age-old anti-Semitic trope? Do we not directly provoke the poor and oppressed to blame the Jews for their misfortunes? One should thus reject the EJA stance not because of some obscene need for “balance” between different forms of racism but on behalf of the very struggle against anti-Semitism.

不仅如此,EJA 的立场还依赖于它自己的交集框架。对某些犹太人占据的特权地位的任何分析都会立即被谴责为反犹太主义,甚至对资本主义的批评也会因为“犹太人”与“富有的资本家”之间的联系而遭到同样的拒绝。旧时的马克思主义理论认为,反犹太主义是一种原始扭曲的反资本主义版本,这一理论被颠倒过来:反资本主义是反犹太主义的面具。但如果这意味着犹太性既特殊又与资本主义密不可分,那么我们不就只剩下了一个古老的反犹太主义的陈词滥调吗?难道我们不是在直接煽动那些贫穷和受压迫的人将他们的不幸归咎于犹太人吗?因此,我们应该拒绝 EJA 的立场,不是因为出于某种对不同形式的种族主义之间“平衡”的恶俗需求,而是为了反对反犹太主义而这么做。

However, the terrible situation in Israel can also give us a reason to hope. Something drastically changed in Israel itself and abroad, even in the US, the most pro-Israel state: even the people who were till now ready to tolerate everything that Israel does are now openly attacking it, and an awareness is rising that things cannot go on as they were till now. Israel presented itself as the only liberal democracy surrounded by authoritarian and fundamentalist Arab regimes, but what it is doing now is getting more and more similar to the worst of hard Arab regimes. The next step is already on the horizon: what Israeli hard-liners want is to turn into second-class citizens their own reformist secularized Jews . . .

然而,以色列的可怕局势也可以给我们一个希望的理由。以色列国内和国外,甚至在美国,这个最亲以色列的国家,发生了某种急剧的变化:甚至那些直到现在准备容忍以色列所做的一切的人,现在也公开地攻击以色列,人们越来越意识到事情不能再像以前那样继续下去了。以色列把自己描绘成周围是专制和极端主义阿拉伯政权的唯一自由民主国家,但以色列现在所做的一切越来越类似于最恶劣的专制政权。下一步已经在眼前:以色列强硬派想要把他们自己的改革世俗犹太人变成二等公民……

This is how one should understand the motto that only a catastrophe can save us: maybe the authoritarian turn in Israel will trigger a strong counter-wave that will defeat it. In the case of Israel, this means that only the publicly asserted solidarity of the three religions of the book (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) can save the emancipatory core of Judaism – at the spiritual level, the greatest victim of the aggressive Zionism will be Jews themselves. What Christian atheism renders possible here is not the overcoming of the existing religions – on the contrary, it opens up the space for a spiritual bond which enables each of them to fl ourish freely. Here atheism plays a key role: the common space in which different religions can thrive is not some vague general spirituality but atheism which renders meaningless the struggle between particular religions.

这就是我们应该如何理解这句格言的:只有大灾难才能拯救我们。我们应该这样理解:也许以色列的权威主义转向会引发一股强大的反浪潮,将其击败。在以色列的情况下,这意味着只有这三本神圣经籍所宣扬的宗教(犹太教、基督教、伊斯兰教)的公开声援,才能拯救犹太教的解放核心——在精神层面上,最受侵略性犹太复国主义伤害的是犹太人自己。基督教无神论在此提供的东西并不是现有宗教的克服——相反,它为一种精神纽带开辟了空间,这种精神纽带使它们每一个都能自由地繁荣发展。在这里,无神论起着关键作用:不同宗教能够繁荣共存的空间并不是某种模糊的一般性精神性,而是无神论,它使特定宗教之间的斗争变得毫无意义。

The Importance of Seeing All Six Feet

看到所有六英尺的重要性

This brings us back to intersectionality, this time the intersectionality of religions themselves – there is a (not too) vulgar joke which perfectly renders its point. The joke begins with a wife and her lover in bed; suddenly, they hear her husband unexpectedly coming home and walking up the stairs, heavily drunk. The lover gets into a panic, but the wife calms him down: “My husband is so drunk, he will not even notice that there is another man in the bed, so just stay where you are!” And, as she predicts, the husband, barely able to walk, just falls onto the bed. An hour or so later, he opens the eyes and says to his wife: “Darling, am I so drunk that I can’t even count what I see? It seems to me there are six legs at the bottom of our bed!” The wife says soothingly: “Don’t worry! Just stand up, walk to the doors in front of the bed and take a clear look!” The husband does this and exclaims: “You are right, there are only four legs! So I can go back and fall asleep again calmly . . .”

这让我们回到了宗教之间的交叉性,这次是宗教本身的交叉性——有一个不太粗俗的笑话完美地表达了这个观点。这个笑话从一个妻子和她情人躺在床上开始,突然,他们听到妻子丈夫意外回家,醉醺醺地走上楼梯。情人很惊慌,但妻子让他冷静下来:“我丈夫喝醉了,他甚至不会注意到床上有另一个人,所以你就待在那儿吧!”正如她所预测的那样,丈夫摇摇晃晃地走进房间,跌倒在床上。一个小时左右后,他睁开眼睛对妻子说:“亲爱的,我醉成这样连数都数不清吗?我觉得床下有六条腿。”妻子安慰他说:“别担心!你就站起来,走到床前门去看看。”丈夫照做了,并喊道:“你说得对,只有四条腿。所以我可以平静地回去再睡一会儿……”这个笑话揭示了一个事实:即使在宗教冲突中,人们仍然需要面对日常生活的现实。

This joke may be vulgar, but it nonetheless involves an interesting formal structure homologous to Jacques Lacan’s joke “I have three brothers, Paul, Robert, and myself.” When fully drunk, the husband included himself into the series, counting himself as one of his brothers; after he was able to adopt a minimally sober external glance, he saw the he has only two brothers (i.e., he excluded himself from the series). What we would expect is that one sees the whole situation clearly when one observes it from the outside, from a safe distance, while when one is immersed into a situation one gets blind for its key dimension, for its horizon that delimitates it; in our joke, however, it is the external position which makes you blind, while you see the truth when you are caught in it (incidentally, the same goes for psychoanalysis and Marxism).

这个笑话可能有点粗俗,但它却涉及到一个与雅克·拉康的笑话“我有三个兄弟,保罗、罗伯特和我自己”类似的有趣的形式结构。当丈夫喝得烂醉如泥时,他把自己也纳入这个系列,把自己当作一个兄弟;在他能够采取一种稍微清醒的外部视角之后,他发现自己只有两个兄弟(也就是说,他把自己排除在这个系列之外)。我们期望的是,当一个人从外部、从一个安全距离观察整个情况时,他会清楚地看到整个情况;而当一个人完全陷入某个情况时,他会失去对关键维度的洞察力,失去对界定该情况的范围的视野;然而在我们的笑话中,正是外部位置让你变得盲目,而当你深陷其中时,你才会看到真相(顺便提一下,这也适用于心理分析和马克思主义)。

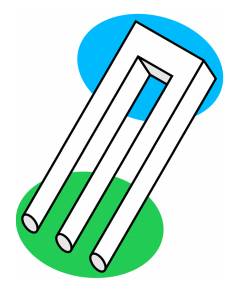

More precisely, the husband doesn’t just exclude himself: his exclusion (standing by the door out of the bed) leads to the wrong inclusion, it makes him confuse the lover’s legs with his own legs: he counts the lover’s legs in the bed as his own, so he returns satisfi ed to the bed, and the lesson he gets is a very cruel one: he condones his wife making love with another man as his own act . . . The irony is, of course, that, in his more sober state, the husband acts as an idiot by way of excluding himself from the series: an unexpected version of in vino veritas . The libidinal truth of such situations is that, even when only the sexual couple is in a bed, there are six legs (the additional two legs standing for the presence of a third agency) – the Lacanian function of the “plus-One” is always operative. Here we should evoke the impossible trident (also known as impossible fork or devil’s tuning fork), the drawing of an impossible object (undecipherable fi gure), a kind of an optical illusion: it appears to have three cylindrical prongs at one end which then mysteriously transform into two rectangular prongs at the other end (see Fig. 1) 14.

更准确地说,丈夫不只是排除自己:他的排斥(站在门口的床)导致错误的包容,这使他混淆情人的腿和自己的腿:他数情人的腿在床上作为自己的,所以他返回满意的床上,他得到的教训是一个非常残酷的:他宽恕他的妻子和另一个男人做爱作为自己的行为。当然,具有讽刺意味的是,在他更清醒的状态下,丈夫就像一个白痴,把自己排除在电视剧之外:一个意想不到的真实版本。这种情况的性欲事实是,即使只有性伴侣在床上,也有六条腿(额外的两条腿代表第三个机构的存在)——“plus one”的拉康 function总是有效的。这里我们应该唤起不可能的三叉戟(也称为不可能叉或魔鬼的音叉),一个不可能的对象(无法辨认 fi 图),一种光学错觉:它似乎有三个圆柱尖头在一端然后神秘地变成两个矩形尖头在另一端(见图 1)14:

在精神分析学家雅克·拉康的理论中,“plus-One”是一个重要的概念,它代表了主体的心理结构中的一种功能。这个“plus-One”可以理解为个体与外部世界的互动中,对自我和他人的感知和理解。

在拉康的理论中,主体是由三个元素构成的:我(I),你(you)和它(it)。其中,“我”代表了个体的自我认同,“你”代表了他人,而“它”则代表了无法理解或无法解释的现象。在主体的心理结构中,“plus-One”的功能就是将这些元素连接起来,形成一个完整的心理结构。

这个“plus-One”的功能是连接和整合这些元素,使得主体能够理解和适应外部世界。它帮助个体感知和理解他人,同时也帮助个体理解那些无法解释的现象。因此,“plus-One”在拉康的理论中具有非常重要的意义,是理解个体心理结构和行为的重要概念。

关键词:

- Lacanian function:拉康的心理功能

- “plus-One”:拉康理论中的重要概念,代表了主体的心理结构中的一种功能

- 自我认同(I):个体对自己的认知和认同

- 他人(you):与个体互动的他人

- 无法理解或无法解释的现象(it):指代那些不能被理解和解释的心理和行为现象

- 连接和整合:指“plus-One”的功能,它帮助个体将自我、他人和无法解释的现象连接起来,形成一个完整的心理结构

- 理解和适应:指个体通过“plus-One”的功能,理解和适应外部世界,包括他人和无法解释的现象。

In our case of the drunk husband, when he is in the bed (blue domain) and looks down, he sees three pairs of legs, but when he steps out (into the green domain) and looks at the bed, he sees two pairs of legs . . .

就我们那个喝醉酒的丈夫来说,他躺在床上(蓝色区域)往下一看,他看到三双脚;当他走出去(进入绿色区域)再往床上一看,却只看到两双脚……

**Figure I.1 **

We should not be afraid to go to the (obscene) end in this direction and imagine the same scene with “virgin” Mary and her husband Joseph. While Joseph is on a drinking binge, Mary has fun in their bed with (the person acting as) the Holy Spirit; Joseph returns home early and crawls to their bed; when he awakens a little bit later, he sees six feet at the bed’s bottom, and then the same story as in our joke goes on – looking at the bed from the door, he sees only two pairs of feet and mistakes the Holy Spirit’s pair for his own . . .

我们不应该害怕朝着这个方向走向(淫秽)结局,想象“圣女”玛利亚和她的丈夫约瑟夫的同样场景。当约瑟酗酒的时候,马利亚在床上玩(扮演圣灵的人);约瑟早早回家,爬到床上;当他醒来后,他看到床底六英尺高,然后我们的笑话继续——从门口看床,他只看到两对脚,误以为圣灵的脚是自己的。

Does something like this not happen when we support Ukraine but ignore the struggle for justice in Ukraine itself? We turn a blind eye to how the Ukrainian struggle is monopolized by the predominant clique of oligarchs, so we shouldn’t be surprised if the post-war Ukraine will be similar to the pre-war corrupted oligarchy colonized by big Western corporations controlling the best land and natural resources – in short, we suffer in the terrible war, but we are blind for the fact that our gains will be appropriated by our enemies, exactly like the drunk husband who condones his wife making love with another man as his own act. How to avoid falling into this trap? On 20–22 June 2023, there was a series of meetings in London coordinated by "Europe, a Patient” association, a pan-European, cross-partisan initiative, with the aim “to protect Ukrainian communities from exploitation after what they have already been through in this war.” Rev. Rowan Williams, Rabbi Wittenberg and Ukrainian NGOs appealed for green, just and citizens-lead recovery:

当我们支持乌克兰而忽视乌克兰本身的正义斗争时,这样的事情不会发生吗?我们视而不见的乌克兰斗争如何垄断的寡头,所以我们不应该感到惊讶如果战后乌克兰将类似于战前腐败的寡头统治殖民的西方大公司控制最好的土地和自然资源——简而言之,我们遭受可怕的战争,但我们是盲目的,我们的收益将被我们的敌人,就像喝醉的丈夫原谅他的妻子和另一个男人做爱作为自己的行为。如何避免掉入这个陷阱?2023 年 6 月 20 日至 22 日,在伦敦举行了一系列会议,由“欧洲,一个病人”协会协调,这是一个泛欧洲的跨党派倡议,目的是“保护乌克兰社区在这场战争中已经经历过什么后免受剥削”。Rev. 罗文·威廉姆斯、维滕贝格和乌克兰非政府组织呼吁绿色、公正和公民领导的复苏:

The challenge for Ukraine and all our international partners is to prevent creating the new breed of oligarchs in the process of post-war reconstruction. . . . Ukrainian people have suffered for too long at the hands of the fossil fuel industry, which are still fi nancing the Russian war machine. 15

乌克兰和我们所有国际伙伴面临的挑战是防止在战后重建过程中创造新的寡头。乌克兰人民遭受化石燃料工业的苦难太久了,而化石燃料工业仍在使用俄罗斯的战争机器。15

Initiatives like this one are needed more than ever today because they unite support of Ukrainian defence with ecological concerns and struggle for social justice. Far from being megalomaniac, such combination of goals is the only realistic option: we can only support Ukraine if we fi ght a fossil fuel industry which relies on Russian oil, and if we simultaneously fi ght for social justice. The combination of different struggles is enforced by circumstances themselves. The destruction of the Kherson dam in early June (with fl ooded villages and mines fl oating in water) brought together war and ecological destruction: the destruction of the environment was consciously used as a military strategy. In itself, this was not something new: already in the Vietnam war, the US army sprayed large forest areas with poisonous gases that defoliated the trees (in order to prevent the Vietcong units hiding in the foliage). What makes the destruction of the Kherson dam worse is that it happened in an era when all sides pay lip service to the protection of environment – we are forced to do this because the threat to our environment is felt more and more in our daily lives. In the fi rst week of June 2023, New York was caught in brown smoke (caused by forest fires in Canada), with people advised to stay indoors and to wear masks if they have to go outside – nothing new for large parts of the so-called Third World:

这样的倡议比以往任何时候都更需要,因为它们将乌克兰国防的支持与生态问题和争取社会正义团结起来。这种目标的组合远不是自大,而是唯一现实的选择:只有我们对抗依赖俄罗斯石油的化石燃料工业,并同时为社会正义而战,我们才能支持乌克兰。不同的斗争的结合是由环境本身来强制执行的。6 月初,赫尔森大坝的破坏(裸露的村庄和地雷漂浮在水中)引发了战争和生态破坏:对环境的破坏被有意识地用作一种军事战略。就其本身而言,这并不是什么新鲜事:在越南战争中,美国军队已经向大片森林地区喷洒有毒气体,使树木落叶(为了防止越共部队躲在树叶里)。使赫尔森大坝的破坏更糟糕的是,它发生在一个双方都口头表示保护环境的时代——我们被迫这样做,因为我们的日常生活越来越感受到对环境的威胁。在 6 月 20 日的第一周

India, Nigeria, Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, Sudan, Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali and central America face extreme risk. Weather events such as massive fl oods and intensified cyclones and hurricanes will keep hammering countries such as Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Haiti and Myanmar. Many people will have to move or die. As the impacts of our consumptio n kick in thousands of miles away, and people come to our borders desperate for refuge from a crisis they played almost no role in causing – a crisis that might involve real fl oods and real droughts – the same political forces announce, without a trace of irony, that we are being ‘fl ooded’ or ‘sucked dry’ by refugees, and millions rally to their call to seal our borders. 16

印度、尼日利亚、印度尼西亚、菲律宾、巴基斯坦、阿富汗、巴布亚新几内亚、苏丹、尼日尔、布基纳法索、马里和中美洲等地面临极高的风险。大规模洪水、加剧的旋风和飓风等天气事件将继续袭击莫桑比克、津巴布韦、海地和缅甸等 18 个基督教无神论国家。许多人不得不迁移或死亡。随着我们的消费行为在千里之外产生影响,人们涌向我们的边境,绝望地寻求避难所,他们几乎未参与引发这场危机——这场危机可能涉及真实的水灾和干旱——相同的政治力量毫无讽刺地宣布,我们正被难民“淹没”或“榨干”,数百万人响应号召,要求封锁我们的边境。16

So why do Western countries, while paying lip service to these problems, continue to cancel measures designed to limit climate breakdown? (Let’s just mention two cases from the US: “legislators in Texas are waging war on renewable energy, while a proposed law in Ohio lists climate policies as a ‘controversial belief or policy’ in which universities are forbidden to ‘inculcate’ their students.” 17 ) To claim that “hard-right and far-right politics are the defensive wall erected by oligarchs to protect their economic interests” 18 is all too simple: ignoring the full scope of the threat to our environment is not limited just to the far Right and/or to big corporations, it includes Leftist conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theorists like to play with alternate history scenarios: what if . . . (the US were not to join the UK and attack Germany in the Second World War; the US were not to attack and occupy Iraq; the West were not to support Ukraine in its struggle against Russian aggression)? These scenarios are not emancipatory dreams about failed revolutions but, on the contrary, profoundly reactionary dreams of making a compromise with brutal authoritarian regimes and thus maintain peace.

那么,为什么西方国家在口头回答这些问题的同时,继续取消旨在限制气候崩溃的措施呢?(让我们来提一下美国的两个案例:“德克萨斯州的立法者正在对可再生能源发动战争,而俄亥俄州的一项法律将气候政策列为‘有争议的信仰或政策’,禁止大学‘灌输’他们的学生。”17)声称“硬右和极右政治防御墙由寡头保护他们的经济利益”18 太简单了:忽视全面的威胁我们的环境并不局限于极右和/或大公司,它包括左翼阴谋论。阴谋论者喜欢玩不同的历史场景:如果……(美国不加入英国,在第二次世界大战中攻击德国;美国不攻击和占领伊拉克;西方不支持乌克兰对抗俄罗斯的侵略)?这些场景不是关于失败革命的解放梦想,相反,是与残暴的威裁政权妥协的极端反动梦想

To understand the “pacifi st” opposition to the NATO military machine, we should return to the situation at the beginning of the Second World War when a similar Right-and-Left stance opposed the entry of the US into the war. The reasons listed were uncannily similar to the reason of today’s “pacifi sts”: why should the US get involved in a far-away war that doesn’t concern it; Rightist discreet sympathy for Germany (no less discreetly supported by Germany); due to the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, the Leftists opposed the war till the German attack on the USSR; the peace offer of Germany to the UK in the Summer of 1940 which was perceived by many as very generous; the worry that the entry of the US into the war would serve the vast industrial-military complex. This reasoning contains a grain of truth, as all good lies do: it is true that the US left the big depression behind only in the course of the Second World War; there are signs that Germany sincerely wanted peace with Great Britain in 1940 (recall the surprising fl ight of Rudolf Hess to England at that time to plea for the peace with Germany).

要理解“和平主义者”对北约军事机器的反对,我们应该回顾第二次世界大战初期的情况,当时类似的左右两派立场反对美国参战。列举的理由与今天的“和平主义者”的理由惊人地相似:美国为什么要参与一场与己无关的遥远战争;右翼对德国的谨慎同情(德国同样不失谨慎地支持它);由于《莱布尼茨-莫洛托夫协定》,左翼在德国进攻苏联之前反对战争;德国在 1940 年夏天向英国提出的和平建议,许多人认为这非常慷慨;担心美国参战将有利于庞大的工业-军事复合体。这种推理包含着一些真理,就像所有好的谎言一样:美国确实是在第二次世界大战期间才摆脱了大萧条的阴影;有迹象表明,德国在 1940 年确实真诚地希望与英国实现和平(回想一下当时鲁道夫·赫斯飞往英国为德国求和)。

The most elaborated version of this line of thought was given in 2009 by Patrick J. Buchanan who argues that, if Churchill had accepted Hitler’s peace offer of 1940, the severity of the Holocaust would have been greatly reduced. (The – often fully justifi ed – critique of Churchill is also shared by the Left: the two recent radical critics of Churchill are David Irving, the Rightist with sympathies for the Nazi Germany, and Tariq Ali, a radical Leftist . . .) Endorsing the concept of Western betrayal, Buchanan accuses Churchill and Roosevelt of turning over Eastern Europe to the Soviet Union at the Tehran Conference and the Yalta Conference. Just as Churchill led the British Empire to ruin by causing unnecessary wars with Germany twice, Bush led the United States to ruin by following Churchill’s example in involving the United States in an unnecessary war in Iraq, and he passed out guarantees to scores of nations in which the United States has no vital interests, which placed his country in a position with insuffi cient resources to fulfi l its promises. 19 What we often hear today is a new variation on this Buchanan motif: the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the ensuing economic decay of post-Soviet states was experienced like a new Versailles treaty and gave birth to the easily predictable desire for revenge. Exactly like Hitler in 1940, Putin repeatedly offered peace to Ukraine; in the fi rst years of his reign, he even proposed that Russia should join NATO . . . Seductive as this line of reasoning may sound (to some, at least), it should be rejected in exactly the same way Fascism has to be fought.

这种思路最详尽的版本出现在 2009 年,由帕特里克·布坎南提出。他主张,如果丘吉尔在 1940 年接受了希特勒的和平提议,大屠杀的严重性就会大大降低。(对丘吉尔的批评——往往完全有理——也得到了左派的认同:最近两位对丘吉尔提出尖锐批评的人是戴维·艾因维林和塔里克·阿里……)布坎南赞同西方背叛的概念,指责丘吉尔和罗斯福在德黑兰会议和雅尔塔会议上把东欧交给了苏联。正如丘吉尔两次与德国发动不必要的战争导致英国帝国走向衰落,布什则追随丘吉尔的榜样,让美国卷入一场不必要的伊拉克战争,并向数十个美国没有重大利益的国家提供保证,这使他的国家处于资源不足的状态,无法兑现承诺。今天我们经常听到的,是布坎南这一主题的新变种:苏联解体和后苏联国家随之而来的经济衰退,就像新的凡尔赛条约一样令人痛苦,并催生了可以轻易预测的复仇欲望。就像希特勒在 1940 年一样,普京一再向乌克兰提出和平建议;在他统治的前几年,他甚至提议俄罗斯加入北约……尽管这种推理听起来很诱人(至少对某些人来说),但应该以同样的方式加以驳斥,就像对付法西斯主义一样。

The problem is that today the hegemonic ideology not only prevents the urgently needed combination of struggles (seeing all six feet, in the terms of our joke); as we have just seen, it even imposes its own false combination in the guise of new conspiracy theories shared by the populist Right and parts of the Left. This new Right/Left alliance denounces eco-panic and “green politics” as a ruse of the big corporations to impose new limitations to the ordinary working people; it rejects helping Ukraine since the military aid serves the NATO industrial-military complex; it denounced anti-Covid measures as an instrument of disciplining the population . . . In a model case of denial, the biggest threat we are confronting today (including the reports of the traces of alien landings) are dismissed as a ploy of the big corporate capital in conjunction with state apparatuses. The message of such a denial is, of course, overtly optimistic, it gives us hope: the return to old normality is easy, we don’t have to fi ght the new dangers, all we have to do is dismiss the threats, i.e., continue to act as if they don’t exist. The proliferation of such denials is the main reason of the sad fact that we live in an era of “democratic recession”:

问题是,今天的霸权意识形态不仅阻止了迫切需要的斗争组合(用我们的笑话来说,只有六脚);正如我们刚刚看到的,它甚至在民粹主义右翼和部分左派共享的新阴谋论的幌子下施加自己的错误组合。这个新的左右联盟谴责生态恐慌和“绿色政治”是大公司对普通劳动人民施加新限制的诡计;它拒绝帮助乌克兰,因为军事援助服务于北约工军联合体;它谴责反新型冠状病毒措施是惩罚民众的手段。在一个否认的典型案例中,20 个基督教无神论,我们今天面临的最大威胁(包括关于外星人登陆痕迹的报道)被认为是大公司资本与国家机构合作的策略。当然,这种否认的信息是明显乐观的,它给了我们希望:恢复旧的正常很容易,我们不必对抗新的危险,我们所要做的就是无视威胁,也就是说,继续像它们不存在一样行动。这种否认的扩散是 t 的主要原因

Authoritarianism is on the rise despite the liberal prediction that the spread of free markets would result in more democracy – that's because capitalism will always defend social hierarchies against the threat of economic equality. 20

尽管自由主义者预测自由市场的扩散将导致更多的民主,但专制主义却有抬头之势——这是因为资本主义总是会捍卫社会等级制度,对抗经济平等的威胁。20

One has to complicate further this claim: the threat to democracy comes also from the false populist resistance to corporate capitalism. This is why the way out of this predicament resides not just in desperately clinging to multi-party liberal democracy – what is needed are new forms of building large social consensus and of establishing a more active link between political parties and civil society. The opposition of liberal democracy and new populists is not the true one; however, this in no way entails that the Trump–Putin camp is better than liberal democracy (in the same sense that it is wrong to have sympathy for Hitler because liberal democracy and fascism are not the true opposites). We should mobilize here the distance that separates tactic from strategy: strategically, liberal democracy is our ultimate enemy, but at the tactical level, we should fi ght with liberal democracy against new populists – in the same way that Communists fought with Western “imperialist” democracies against Fascism in the Second World War, knowing very well that imperialism is their ultimate enemy.

人们必须使这一说法进一步复杂化:对民主的威胁也来自于对企业资本主义的虚假民粹主义抵制。这就是为什么摆脱这种困境的方法不仅仅是拼命坚持多党自由民主——需要的是建立大的社会共识,以及在政党和公民社会之间建立更积极的联系。自由民主和新民粹主义者的反对并不是真正的反对;然而,这并不意味着特朗普-普京阵营比自由民主更好(从同样的意义上说,同情希特勒是错误的,因为自由民主和法西斯主义并不是真正的对立面)。我们应该动员这里的距离分离策略:战略,自由民主是我们的终极敌人,但在战术层面上,我们应该与自由民主对抗新民粹主义者——以同样的方式,共产党与西方“帝国主义”民主反对法西斯主义在第二次世界大战中,非常清楚帝国主义是他们的终极敌人。

Did we not drift far away from our starting point, the notion of Christian atheism, and get lost in a mixture of political comments? No, because these comments demonstrate precisely how Christian atheism works as a political practice. Raffaele Nogaro (a priest from Rome who was 98 in 2022) claimed that Jesus is the “New Man” who loves everyone without distinction of person, whatever his culture, the colour of his skin, his religion or the depth of his atheism – everyone is asked by Jesus the same question: “Who do you say that I am?” 21 Note that for Nogaro, Christ is not a fi gure of authority telling people what they are: he is asking them about what they are saying that He is. And one should not take this as a cheap rhetorical trick in the sense of “I know who I am, the son of God, I just want to check if you know this.” Christ is aware that, in some way, his very existence is at stake not only in what and how people are talking about him, but above all in how they act (or don’t act) in society. Each of us has to give a reply to Jesus’ question from one’s existential depth, and then enact this reply.

难道我们没有偏离了我们的起点,基督教无神论的概念,并迷失在各种政治评论中吗?不,因为这些评论准确地证明了基督教无神论作为一种政治实践的作用。拉斐尔诺加罗\(罗马牧师 2022 年 98\)声称耶稣是“新男人”没有区别的人,无论他的文化,他的肤色,他的宗教或无神论的深度——每个人都问耶稣同样的问题:“你说我是谁?”请注意,对诺加罗来说,基督并不是一个权威的人物,他会告诉人们他们是什么:他是在问他们,他们在说他是什么。人们不应该把这当作一种廉价的修辞技巧,比如“我知道我是谁,上帝的儿子,我只是想看看你是否知道。”基督意识到,在某种程度上,他的存在不仅关乎人们如何谈论他,最重要的是他们在社会中的行为(或不行为)。我们每个人都必须从一个人的存在主义的深度来回答耶稣的问题,然后再制定这个回答。

LET A RELIGION DEPLETE ITSELF

1. 让宗教自行消亡

Who Can't Handle the Truth?

谁不能处理真相 ?

Sometimes, even the lowest blockbuster trash purveys a useful lesson.Kevin Costner’s Postman (otherwise a dismal failure) focuses on the structural necessity of an ideological Lie as the condition to reconstitute the social link – the fi lm’s premise is that the only way to recreate the Restored USA after the global catastrophe is by pretending that the Federal Government still exists , by acting AS IF it exists, so that people start to believe in it and behave accordingly, and the Lie becomes Truth (the hero sets in motion the reconstitution of the USA by starting to deliver mail as if he acts on behalf of the US postal system). This brings us to the paradoxical temporality of truth.

有时,即使是最低俗的大片垃圾也能教给我们一些有用的教训。凯文·科斯特纳的《邮差》(原本是一部惨败的电影)着重探讨了意识形态谎言在结构上的必要性,作为重建社会联系的条件——电影的前提是,全球灾难后重建恢复的美国唯一的方法就是假装联邦政府仍然存在,假装它还在发挥作用,这样人们就会开始相信它并相应地行事,谎言就会变成真理(英雄通过开始投递邮件,仿佛代表美国邮政系统,从而启动重建美国的进程)。这让我们想到了真理的矛盾时间性。

Most of us know well the culminating moment of A Few Good Men (Rob Reiner, 1992) when Tom Cruise addresses Jack Nicholson with “I want the truth!”, and Nicholson shouts back: “You can’t handle the truth!” This reply is more ambiguous than it may appear: it should not be taken as simply claiming that most of us are too weak to handle the brutal reality of things. We thus have to get rid of the metaphor of the Real as the hard core of reality (the way things “really are in themselves”) accessible to us only through multiple lenses of how we symbolize reality, of how we construct it through our fantasies and cognitive biases. In the opposition between reality (“hard facts”) and fantasies (illusions, symbolic constructs), the Real is on the side of illusions and fantasies: the Real, of course, by defi nition resists full symbolization, but it is at the same time an excess generated by the process of symbolization itself. Without symbolization, there is no Real, there is just a fl at stupidity of what is there. Another (perhaps the ultimate) example: if someone were to ask a witness about the truth of the Holocaust, and the witness were to reply “You can’t handle the truth!”, this should not be understood as a simple claim that most of us are not able the process the horror of Holocaust. At a deeper level, those who were not able to handle the truth were the Nazi perpetrators themselves: they were not able to handle the truth that their society is traversed by an all-encompassing antagonism, and to avoid this insight they engaged in the murdering spray that targeted the Jews, as if killing the Jews would re-establish a harmonious social body. What nonetheless complicates the things even more is that the “truth” evoked by Nicholson is not simply the reality of how things stand but a more precise fact that our power (not just the military) has to follow illegal unwritten rules and practices (the “Code Red” in the fi lm) to sustain its legal system – this is the truth soft liberals are not able to handle. Such a notion of truth involves a paradoxical temporal structure:

我们大多数人都很熟悉《好人寥寥》(罗伯·莱纳,1992)的结尾时刻,汤姆·克鲁斯对杰克·尼科尔森说“我要真相!”,尼科尔森回吼:“你承受不了真相!”这个回答比它表面看起来更具歧义:它不应该被简单地理解为大多数人都太脆弱而无法承受事物的残酷现实。因此,我们必须摆脱将真实作为现实的核心(事物“真正是他们自己”)的隐喻,我们只能通过我们如何象征现实、我们如何通过我们的幻想和认知偏见来构建它。在真实(“硬事实”)和幻想(幻想、象征性构造)之间的对立中,真实在幻想和想象的一边:当然,根据定义,真实总是抵制完全的符号化,但它也是符号化过程本身产生的过剩。没有符号化,就没有真实,只有存在的平庸愚蠢。另一个(也许是最终)例子:如果有人问一个证人关于大屠杀的真相,而证人回答“你承受不了真相!”,这不应该被理解为简单地说大多数人都无法处理大屠杀的恐怖。在更深层次上,那些无法处理真相的人正是纳粹肇事者本身:他们无法面对真相,即他们的社会充满了无所不在的敌对情绪,为了避免这种洞察,他们参与了针对犹太人的屠杀,仿佛杀死犹太人就能重建和谐的社会。然而使事情更加复杂的是尼科尔森所引述的“真理”不仅仅是事情的真相,而是我们的力量(不仅仅是军事力量)必须遵守非法的、不成文的规则和做法(电影中的“红色准则”)来维持法律体系——这就是软心肠的自由派人士无法面对的真理。这种真理包含着一种矛盾的时间结构:

Traditionally, truth seems to have posed as a regulative idea of a state of direct accord . However, this aspired directness was then compensated with the infinite postponement of achieving it. It is perhaps time to reverse this formula, hence, to conceive truth in the frame of indirectness, and then let it happen fully in the here and now. A mere change of perspective enables us to detect an entirely different ‘life of truth.’ Instead of conceptualizing ‘truth’ as perpetually approximating to a certain idealized state of full satisfaction, we will rather shift our attention to the instances of truth emerging actually within a particular historical reality, either inciting events of great magnitude and irreversible temporality, or producing incontrovertible and inextricable knots and excesses in everyday life, or producing unexpected surpluses in the flukes and fl aws of speech. Truth seems impossible and is at the same time inevitable; it gives itself the veneer of eluding our grasp, but then crops up abruptly, even accidentally, and engages us in its discursive bindingness, its compulsory and inescapable effects, its political force and historical exigency, and perhaps its logical necessity. 1

传统上,真理似乎被视为直接一致状态的规范理念。然而,这种渴望的直接性随后被无限期地推迟实现所补偿。或许是时候改变这种公式了,因此,我们应该在间接性的框架中构思真理,然后在此时此地充分实现它。仅仅改变视角就能使我们察觉到完全不同的“真理生活”。我们不再将“真理”概念化为无限接近某种理想化的完全满足状态,而是将注意力转向在特定历史现实中出现的真理实例,这些实例可能引发重大、不可逆转的临时性事件,或者在日常生活中产生无可辩驳、无法摆脱的纠结和过度,或者在言语的波动和缺陷中产生意想不到的盈余。真理似乎是不可能的,同时又是不可避免的;它似乎在逃避我们的掌握,但突然出现,甚至偶然出现,并使我们陷入其论述的约束性、强制性和不可避免的影响、政治力量和历史紧迫性,以及或许其逻辑必然性。

Truth is thus like jouissance (Jacques-Alain Miller once referred to truth as a younger sister of jouissance ): impossible and inevitable at the same time. The worst thing one can do apropos truth is to conceive it as something – an unknown X – we gradually approach in an infi nite process of approximation, without ever reaching it. There is no place for any type of the poetry of lack here, of how we ultimately always miss the fi nal truth – this is not what Lacan means when he asserts, at the beginning of “Television,” that truth can only be half-told: “I always speak the truth. Not the whole truth, because there’s no way, to say it all. Saying it all is literally impossible: words fail. Yet it’s through this very impossibility that the truth holds onto the real.” 2 We repress truth, it eludes us, but it is always-already here in its effects, as half-said – say, as a symptom which undermines the hegemonic structure of our symbolic space. It is not only impossible to tell the whole truth, it is even more impossible to fully lie: truth always catches up with us in the cracks and displacements of our lies. 3

真理就像快乐(雅克-阿兰·米勒曾把真理比作快乐的妹妹):在同一段时间里既不可能又不可避免。最不能做的事情就是认为真理是一种我们通过无限接近的过程逐渐接近的某种东西——一个未知的 X——我们永远无法达到它。这里没有空间容纳任何类型的缺乏诗意,我们最终总是错过最终真理——拉康在“电视”开始时断言,真理只能被半说出:我总是说出真相。不是全部真相,因为没有办法把它都说出来。说出来全部是字面上的不可能:词句失效。然而,正是这种不可能性使得真理抓住真实。我们压抑真理,它逃避我们,但它在效果中总是已经在这里,就像半说出的——例如,作为一种破坏我们符号空间霸权结构的症候。不仅不可能说出全部真相,甚至完全撒谎也是不可能的:真理总是在我们的谎言的裂缝和位移中追赶上我们。4

According to Bertolt Brecht, if we directly strive for happiness, happiness escapes us, whereas it catches us as soon as we stop striving for it (“Yes, run for happiness/ But don’t run too hard/ For all run after happiness/ Happiness is running after.”) Is the same not also the case with truth? If we run after truth too hard, truth will stay behind, ignored. Can we say the same about God? Is God a lie, a product of our collective fantasizing, which gives birth not to his actual existence but to an actual social order based on his teachings and commands, an actual order in which institutions and habits are religiously grounded? It’s not as simple as that: in the modern secular societies in which god is proclaimed dead, he returns as a disavowed ghost surviving his death – how?

根据贝托尔德·布莱希特的说法,如果我们直接努力追求幸福,幸福就会从我们身边溜走,而当我们停止追求它时,幸福就会抓住我们(“是的,为幸福而奔波/但不要太努力/因为所有人都在追逐幸福/而幸福却在追逐。”)。同样的情况是否也发生在真理身上?如果我们过于努力地追求真理,真理就会躲在我们身后,被忽视。那么我们能否同样地谈论上帝?上帝是一个谎言吗?是我们集体幻想的产品,它不是产生于他的实际存在,而是产生于基于他的教义和命令的实际社会秩序,一个制度与习惯都基于宗教信仰的实际秩序?事情并没有那么简单:在宣布上帝已死的现代世俗社会中,他以一种被否认的幽灵形式复活——他是如何复活的?

God Is Undead 4 , the defi nitive book on the ambiguous relationship between Lacanian psychoanalysis and atheism, is a substantial debate between Adrian Johnston (who advocates dialectical materialism) and Lorenzo Chiesa (who insists that agnostic scepticism is the only consistent stance of true atheism). 5 I agree with Chiesa that the direct assertion of indifferent ontological multiplicity, of not-One which precedes any identity, is insuffi cient – Johnston seems to move in this direction, which is why his “transcendental materialism” bypasses all too easily the transcendental dimension and comes dangerously close to simple materialist ontology. However, in contrast to Chiesa, I think that the oscillations that characterize the relationship between the One and the not-One leave no space open for a possible religious outcome: what oscillations signal is an irreducible gap, crack, in the ontological edifi ce of reality itself. This crack is not the crack between our multiple symbolizations of reality and this reality “in itself,” it is located into the very heart of reality itself. And the space of theosophy is located in the gap that makes the transcendental dimension irreducible to ontology – vulgari eloquentia , we cannot ever fully account for our transcendental horizon in the terms of universal ontology since every ontological vision of the whole of reality falls under the scope of the transcendental, and this is what makes all general ontologies from Spinoza’s to Deleuze’s ultimately untenable.

《上帝已死 4》是关于拉康精神分析学与无神论之间模糊关系的确切定义的权威书籍,是一场由阿德里安·约翰斯顿(他主张辩证唯物主义)和洛伦佐·切塞(他坚持不可知怀疑论是真正的无神论的唯一一致立场)之间的实质性辩论。5

我同意切塞的观点,认为直接断言无差别的存在论多元性,即任何身份之前的不一,是不够的-约翰斯顿似乎朝这个方向发展,这就是为什么他的“先验唯物主义”过于轻易地避开了先验维度,并危险地接近简单的唯物主义本体论。然而,与切塞不同的是,我认为在“一”与“不一”之间的关系中所特有的摆动为可能的宗教结果留出了空隙:基督教无神论。

这种摆动所标志的是在现实本体存在论的大楼中一个不可逾越的裂缝、裂痕。这个裂痕不是在我们对现实的多元符号化与“自在”现实之间的裂痕,而是在现实自身的心脏部位。而神学的空间位于使先验维度无法还原为本体论的空隙中-换句话说,我们无法用普遍本体论的术语完全解释我们的先验视域,因为对现实整体的所有本体论设想都超出了先验的范围,这就是为什么从斯宾诺莎到德勒兹的一般本体论最终是不可行的。

The oscillation on which Chiesa focuses can be reduced to the tension between the enunciated and the (process of its) enunciation: when we assert the irreducible non-One as the ultimate truth of being, our very position of enunciation functions as that of a One able to grasp all of reality in its truth, and vice versa, when we try to speak about the One as the supreme divine reality our position of enunciation necessarily gets inconsistent, caught in contradictions. In philosophy, this tension appears as the tension between the reality we confront and transcendental horizon through which we perceive reality – the supreme example: we can convincingly argue and demonstrate that there is no free will, that freedom is a “user’s illusion,” but our very practice of arguing implies that we act as free, trying to convince others to freely accept our arguments. So even if we know we are not free we act as if we are free. However, the refl exive shift from the enunciated content back to our process of its enunciation should not be taken as a step from illusion to truth: yes, we act and argue as if we are free, but cognitive science can explain how this illusion of freedom arose. It is a mega-achievement of modern science to suspend our subjective engagement and to focus on “objective reality”: scientifi c results should not be judged by “whom they serve” or by reference to the subjective economy of those who elaborate them. When Lacan says that science forecloses the subject, this is not a negative judgement pointing out that science misses something but a gesture that sustains the very space of modern science. In short, scientifi c content cannot be “transcendentally deduced” from subjective activity (what Fichte tried to do), the oscillation between the two is irreducible. This is why what Chiesa calls irreducible oscillation is what I refer to as the irreducible ontological parallax. 6

齐泽克所关注的振荡可以被归结为所宣称与 (其过程)宣称之间的张力:当我们断言存在的不可约减的非一就是存在的终极真理时,我们的宣称位置起着这样一个一的作用,即能够把握现实的所有真理,反之亦然,当我们试图把一当作至高无上的神圣现实来谈论时,我们的宣称位置必然变得不一致,陷入矛盾。在哲学中,这种张力表现为我们面对的现实与我们感知现实之超越论地平线之间的张力——最高例子:我们可以令人信服地论证和证明不存在自由,自由是“用户的幻觉”,但我们的辩论实践暗示我们作为自由行动,试图说服别人自由地接受我们的论点。因此,即使我们知道我们不是自由的,我们也会表现得好像我们是自由的。然而,从所宣称的内容返回到我们的宣称过程,这种反思性转变不应被视为从幻觉到真理的步骤:是的,我们表现得好像我们是自由的,但认知科学可以解释这种自由幻觉是如何产生的。现代科学暂停我们的主观参与并专注于“客观现实”,这是它的巨大成就:科学成果不应由“他们为谁服务”或由阐述它们的人的主观经济来评判。当拉康说科学阻断了主体时,这不是一个负面判断,指出科学错过了什么,而是一个手势,维持着现代科学的空间。简而言之,科学内容不能从主观活动中“先验地推断”(费希特试图这样做),两者之间的振荡是不可化约的。这就是为什么齐泽克称之为不可化约的振荡,而我把它称为不可化约的本体视差。6

Subjectivity in Afropessimism

非洲悲观论中的主观性

Where does theosophy enter here? It allows us to challenge the standard view according to which “objective reality” is out there, a transcendent object we are gradually approaching. What we experience as “objective reality” is always-already transcendentally constituted, so that we only touch the Real beyond or beneath reality when we experience “the night of the world,” i.e., when reality dissolves and the only thing remaining is the abyss of subjectivity. It may appear that, when we talk about the ontological void of “inhuman” subjectivity, we are dealing with a transcendental-ontological category with no direct political implications: political projects and choices are ontic decisions and identifi cations which take place within an ontological horizon given in advance . . . However, there are moments of radical political action in which the ontological dimension as such is at stake; in theory, politics is raised at this level in so-called Afropessimism. Frank B. Wilderson III 7 elaborated the most convincing version of Afropessimism by way of posing questions that the predominant liberal Humanism avoids:“simply put, we abdicated the power to pose the question—and the power to pose the question is the greatest power of all”(ix). The question is: humanism presents itself as universal, all-encompassing, but this universality is already grounded in an exclusion. It is not just that humanism imposes a Western standard of being-human which reduces subaltern Others to a lower level of humanity; Humanism is based on the exclusion of a large group of humans (Blacks) as non-Human. outside the hierarchical sphere of Humanity, while Asians and Latinos are “lesser humans” who can demand full Humanity. (The young Gandhi played this game: when he protested against apartheid in South Africa, he didn’t demand legal equality of Whites and Blacks, he just wanted the large Indian minority to get the same rights as the Whites.) Plus one should raise here another question which is very relevant in our multicentric world with the stronger position of Asia: are Blacks non-Human just from the standpoint of European Whites? What about Asians – what are Blacks for them? Also non-human?

神秘主义在此处有何介入?它让我们质疑那种标准观点,即“客观现实”就在那里,一个我们正在逐渐接近的超越对象。我们所经历的“客观现实”总是已经超越性地构成,因此,只有在我们体验“世界之夜”时,我们才能触及超越或隐藏在现实之上的真实——也就是说,当现实消散,唯一剩下的是主观性的深渊。当我们谈论“非人”主观性的本体论空虚时,似乎我们在讨论一个没有直接政治含义的先验超越论-本体论范畴:政治项目和选择是本体论预给视域内的本体论决定和认同……然而,在政治行动的极端时刻中,本体论维度本身处于危险之中;理论上,政治在这一层面上升到了所谓的非裔悲观主义。弗兰克·B·威尔代森三世通过提出主导的自由人文主义避免的问题来阐述非裔悲观主义中最令人信服的版本:“简单地说,我们放弃了提出问题——而提出问题的能力是一切中最伟大的力量”(ix)。问题是:人文主义呈现为普遍的、无所不包的,但这种普遍性已经植根于一种排斥。人文主义不仅强加了一种西方的“人性”标准,将从属的他人贬低到较低层次的人性;而且人文主义还基于一大群人的排斥(黑人),他们被排除在人类等级体系之外,而亚裔和拉丁裔则是“较次等人”,他们可以要求享有完全的人性。(年轻的甘地就玩这个游戏:当他抗议南非的种族隔离时,他并没有要求白人和黑人享有平等的法律权利,他只是希望印度少数群体能获得与白人相同的权利。)此外,我们应该在这里提出另一个问题,这个问题在我们这个亚洲地位日益提高的多中心世界中非常相关:黑人仅仅从欧洲白人的角度来看是非人类吗?亚洲人呢——对他们来说,黑人又如何?也是非人类吗?